[EN] Cell phones are worse than refrigerators

[EN] Cell phones are worse than refrigerators

Matéria originalmente publicada em português na edição nº1426 do Jornal Notícia. Traduzida para o inglês pela equipe do Paraná Fala Inglês (PFI).The philosopher Lucius Annaeus Seneca, born in Cordoba (Spain), once said: “Natural necessity has its own limits, while artificial necessities and those derived from mere pleasure know no bounds”. Considering that he lived in the first century after Christ, it is disturbing to realize how relevant his words are today.

This is the conclusion reached by Professor Andréa Luísa Bucchile Faggion, from the Department of Philosophy at UEL. In addition to being a researcher in the Philosophy of Law, during her teaching career and in the development of the Research Methodology course, she identified certain challenges faced by undergraduate and graduate students, such as a lack of focus, discipline, and organization, which made it more challenging to carry out research, a final paper, or an article.

Professor Faggion attributes these problems to deeper, more systematic causes rooted in the contemporary social structure itself. These issues are not limited to the academic sphere but extend to work and social life in general. “It’s a problem of our time. Work has no end, no defined hours or location. You can and are expected to work anytime, anywhere”, she explains.

She explains that, in the past, work used to follow a natural rhythm, with time set aside for everything. In most cases, work activities ended at the close of the day. However, inventions such as the electric light bulb, for example, made night shifts possible in factories, shops, and schools – creating more opportunities to produce, produce, and produce. The problem, she points out, is that resources are limited, both in terms of nature and human capacity, and thus cannot keep up with so much demand. Furthermore, everything perpetuates a model of subordinate relations and overload.

In short, working hard has become a lifestyle. Worse still, this lifestyle has influenced other aspects of social life. As a result, people work to the point of exhaustion, hold multiple jobs, and juggle work, studies, and parenting – all to maintain a certain status, defined by that often-quoted phrase of unknown origin: “Status is buying things you don’t need with money you don’t have to impress people you don’t like, pretending to be a person you’re not”.

Social Media

In this regard, social media is the realm of appearance. “People feel obliged to react to everything they see, afraid of no longer being noticed, liked, or commented on. The curious thing is that a person may have hundreds of ‘friends’, but the vast majority of them wouldn’t even notice if they stop posting.”, comments Professor Faggion.

For the professor, social media is a “casino technology” – a place with no clocks and no walls, designed to make people lose track of time and stay there indefinitely.

In a reality like this, how can you set priorities? “If you have more than three priorities, you have none,” the professor asserts. To her, some plan or goal will always be set aside for another: career, travel, new car, family, home ownership, marriage… It’s impossible to “prioritize” everything, and trying to do so will only lead to exhaustion and possibly illness.

The same idea applies to the work routine: no one truly accomplishes multiple tasks “at the same time”, says Andréa. At most, they do it alternately, focusing on one and then the other – which is also not ideal, even though it may be praised: “Wow, so-and-so does three things at the same time”. Not at all. Nor should anyone do it. However, we do feel this pressure to be better at everything, says the professor.

Likewise, students, workers, and others are increasingly unable to pay attention to their interlocutors. “People don’t listen. They just wait for their turn to speak”. Not long ago, the director of the Central Bank, Roberto Campos Neto, compared President Lula, who is more attentive, to his predecessor: “Bolsonaro would get distracted in three minutes”, he told the press.

In her opinion, the outcome of work should have value without the cost being exhaustion. According to the professor, bureaucracy is one of the major obstacles, considered broadly: beyond reports and long, frequent meetings, as well as working groups and committees, which are exhausting and often counterproductive. “These are hours and hours in which the employee could be working on what really matters but is instead taken away to carry out bureaucratic activities,” she ponders.

Productivism

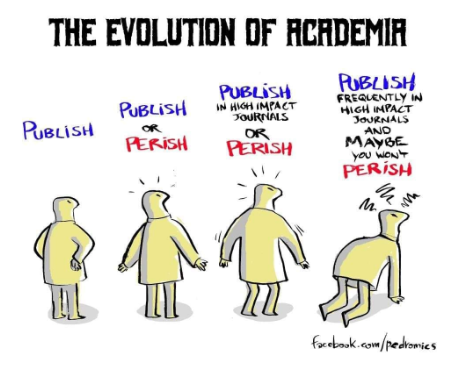

Professor Faggion. points out that managers (bosses, etc.) contribute to this scenario by adopting a productivist ideal. This means they adhere to a doctrine that views the quantitative increase in production as the primary objective of the evolution of social, political, and economic structures. The cartoon on this page illustrates a story that circulates in university corridors.

Academic productivism has been the subject of study and criticism since the 1990s. While some view it positively, others call it a “necessary evil”, as it at least ensures that researchers maintain a steady pace of production – which, of course, does not guarantee the quality of the work produced.

Saying no

One of the solutions for this problem, according to Professor Andréa Faggion, is to say “no”, even to important things. “It’s sad, it’s difficult, but you have to say ‘no’ sometimes”, she asserts. Only then, with organization and planning, is it possible to produce quality work. After all, she argues, planning is more exciting than execution. Or, to borrow a saying, “Anticipation sometimes exceeds realization”.

Another approach, much bolder (some might say radical), is to reduce screen time. Professor Faggion shares that she no longer has a profile on any social media platform and feels happier this way: “It improved my quality of life”, she summarizes.

According to her, social networks provoke a sense of comparison among people (success, travel, etc.), which diminishes the joy of those who lack such experiences. She suggests, “Take a month-long break from social media. Many people won’t even notice your absence”.

This is because, she says, those relationships aren’t authentic. “Social networks take your focus away. It’s an addiction – an addiction to dopamine, a craving for new things and likes – that robs you of your ability to focus and concentrate. The cell phone is worse than the refrigerator,” she concludes.

In practice

Professor Faggion puts these ideas into practice with her students, especially her advisees. “There’s no demanding work all the time, but there is a schedule and a good conversation at the start of the study”, she explains. For the professor, unforeseen events don’t really exist – everyone knows that some problem will arise, they just don’t know what or when, and that’s part of the research process.

In addition to planning, she emphasizes the need not to let tasks pile up or postpone them until the last minute. After all, there can always be that inevitable conflict between what’s most important and what’s most urgent. For her, a good research project is not the product of genius but of methodical work. So far, she’s satisfied with the quality of the Master’s and Doctoral theses she supervises. Good research, according to her, is not a “patchwork quilt” of references, or a summary of various authors, but involves classifying, grouping, creating a taxonomy, and being able to present knowledge in one’s own words.

Andréa is also currently the coordinator of undergraduate theses in Philosophy. She develops research projects in Ethics, and Political and Legal Philosophy. Additionally, she has a YouTube channel (@AndreaFaggion) where she offers guidance on scientific work. Everything is well planned.

Versão em inglês: Ana Paula Luiz dos Santos Aires. Revisão: Raquel Prette. Supervisão: Fernanda Machado Brenner. Programa Paraná Fala Inglês (PFI).

Matéria originalmente publicada em português na edição nº1426 do Jornal Notícia: “O celular é pior que a geladeira”.